Rescue of survivors: Yazidi women. The variability of the experience gained or the project “only for women”

Author of the article - Thomas McGee

Part -3

“I have seen much benefit. They gave us our own house. I have attended school. For me, school is better than a psychologist. What Germany did for me was very big. Nobody else has done such a thing for us. It was really big.”

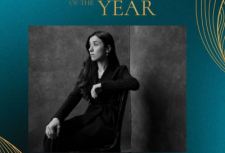

During conversations with women participants in the programme, they presented interesting perspectives on adjusting to life in Germany as well as reflecting on their involvement. It was striking to notice the variation of experience, both in terms of descriptions of services received and the women’s own assessments of their wellbeing. Some, like the young, unmarried survivor in Stuttgart quoted above, presented narratives of remarkable personal transformation and integration into German society. Those with serious medical conditions expressed clear gratitude for operations undergone in Germany, highlighting that necessary treatment was sometimes simply unavailable in Kurdistan. Meanwhile, life in Germany has provided an opportunity for some participants in the programme to take charge of their lives, assert their independence, and even sometimes to establish public advocacy profiles for themselves, something that would have been almost unimaginable back in the conservative, patriarchal context of Kurdistan. The best-known example of this is Nadia Murad, now the first United Nations Goodwill Ambassador for the Dignity of Survivors of Human Trafficking. Her high-profile activities exemplify how the diaspora context can “offer Yezidis the possibility of the creativity and reflexivity of an independent and enriching life”. This, however, also comes with the realisation that there is sometimes community pressure or a sense of uncomfortable duty to ensure that the story of the Yezidi genocide is heard. Indeed, one Yezidi survivor in Germany told me how she felt nervous that a Facebook page in her name was being operated by a group of activists without her having control over the posted content.

While women with more severe psychological conditions had generally benefitted from specialist care in Germany, other survivors complained that they had not received a single counselling session since arriving in the country. This may be partially explained by the lack of local capacity available (in terms of interpreters and social workers), especially given the demand on services following the large migrant/refugee influx since 2015. Nonetheless, it is somewhat ironic that a programme premised on the provision of intensive psychological support unavailable in Kurdistan has, in certain cases, failed to deliver these services. According to Kizilhan, only about one third of participants were deemed ready to begin therapy, noting that some, particularly older women, are reticent to engage in healing practices that appear “too foreign”. It is possible that some of the women have misconceptions about what psychological treatment entails, increasing the need for cultural-sensitive approaches to recovery.

There also appears to be significant variation in the standards and kinds of housing provided to survivors and their accompanying family members. While the programme description asserts that women are accommodated in “a secured and separate building for the beneficiaries only, in order to reduce possible re-traumatization if they lived together with foreign male refugees” (SMBW, 2016a), it is clear that in reality participants experienced a diverse range of living situations. In contrast to those who were accommodated in comfortable, detached houses (or even villas), one woman shared with me her sense of isolation living alone in a camp-like setting alongside young male refugees from other nationalities. Others felt stigmatised through their accommodation in the annex of a psychiatric hospital in Stuttgart. “Youths shout that we are crazy and throw things at the building,” said one such woman. Speaking to Dr Kizilhan, he confirmed that establishing standards of accommodation has proved challenging: “each of the participating municipalities committed to host a number of survivors according to available options. Some had little more than an old school or hospital building.” He added that the 2015 refugee influx has increased demand on municipal housing and explained that lack of available accommodation is a problem affecting Germany more generally.

A more frequent complaint was that the participants of the programme were dispersed across the large area of Baden-Württemberg with little consideration for keeping sisters and other relatives in proximity to one another. Two sisters living hours away from each other described how they had repeatedly pleaded to be relocated closer together, while acknowledging that the authorities have responded positively to other similar requests. Additionally, several women explained that the Heimat (residence) where they were staying was a kind of convent run by nuns who sometimes did not permit them to go out or receive visitors.

Here it is interesting to examine the basis for exclusion of adult men from participation in travel to Baden-Württemberg, and by extension in the healing process for the female survivors the programme aims to support. Indeed, the complaint that husbands and adult sons were unable to accompany the women was consistently heard during my interviews with participants. Likewise, a journalist who covered the programme from both Duhok and Germany stated that this was “the one complaint about the program many of the women raised to me.” This article considers three main factors as contributing to and possibly explaining the “women-only” design of the Baden-Württemberg programme, each bringing implications for the gendered construction of the Yezidi survivor:

1) dominant discourse on female victimization;

2) perceptions about the optimal conditions for women’s recovery

3) structural limitations informed by wider migration dynamics and discourse in Germany.

All this suggests that on" paper " the project was ready to accept Yazidi women, but in fact it turned out that all the nuances were not fully thought out.

Tags: #yazidisinfo #newsyazidi #aboutyazidi #genocideyazidi #yazidigermany

Rescue of survivors: Yazidi women. The variability of the experience gained or the project “only for women”

Author of the article - Thomas McGee

Part -3

“I have seen much benefit. They gave us our own house. I have attended school. For me, school is better than a psychologist. What Germany did for me was very big. Nobody else has done such a thing for us. It was really big.”

During conversations with women participants in the programme, they presented interesting perspectives on adjusting to life in Germany as well as reflecting on their involvement. It was striking to notice the variation of experience, both in terms of descriptions of services received and the women’s own assessments of their wellbeing. Some, like the young, unmarried survivor in Stuttgart quoted above, presented narratives of remarkable personal transformation and integration into German society. Those with serious medical conditions expressed clear gratitude for operations undergone in Germany, highlighting that necessary treatment was sometimes simply unavailable in Kurdistan. Meanwhile, life in Germany has provided an opportunity for some participants in the programme to take charge of their lives, assert their independence, and even sometimes to establish public advocacy profiles for themselves, something that would have been almost unimaginable back in the conservative, patriarchal context of Kurdistan. The best-known example of this is Nadia Murad, now the first United Nations Goodwill Ambassador for the Dignity of Survivors of Human Trafficking. Her high-profile activities exemplify how the diaspora context can “offer Yezidis the possibility of the creativity and reflexivity of an independent and enriching life”. This, however, also comes with the realisation that there is sometimes community pressure or a sense of uncomfortable duty to ensure that the story of the Yezidi genocide is heard. Indeed, one Yezidi survivor in Germany told me how she felt nervous that a Facebook page in her name was being operated by a group of activists without her having control over the posted content.

While women with more severe psychological conditions had generally benefitted from specialist care in Germany, other survivors complained that they had not received a single counselling session since arriving in the country. This may be partially explained by the lack of local capacity available (in terms of interpreters and social workers), especially given the demand on services following the large migrant/refugee influx since 2015. Nonetheless, it is somewhat ironic that a programme premised on the provision of intensive psychological support unavailable in Kurdistan has, in certain cases, failed to deliver these services. According to Kizilhan, only about one third of participants were deemed ready to begin therapy, noting that some, particularly older women, are reticent to engage in healing practices that appear “too foreign”. It is possible that some of the women have misconceptions about what psychological treatment entails, increasing the need for cultural-sensitive approaches to recovery.

There also appears to be significant variation in the standards and kinds of housing provided to survivors and their accompanying family members. While the programme description asserts that women are accommodated in “a secured and separate building for the beneficiaries only, in order to reduce possible re-traumatization if they lived together with foreign male refugees” (SMBW, 2016a), it is clear that in reality participants experienced a diverse range of living situations. In contrast to those who were accommodated in comfortable, detached houses (or even villas), one woman shared with me her sense of isolation living alone in a camp-like setting alongside young male refugees from other nationalities. Others felt stigmatised through their accommodation in the annex of a psychiatric hospital in Stuttgart. “Youths shout that we are crazy and throw things at the building,” said one such woman. Speaking to Dr Kizilhan, he confirmed that establishing standards of accommodation has proved challenging: “each of the participating municipalities committed to host a number of survivors according to available options. Some had little more than an old school or hospital building.” He added that the 2015 refugee influx has increased demand on municipal housing and explained that lack of available accommodation is a problem affecting Germany more generally.

A more frequent complaint was that the participants of the programme were dispersed across the large area of Baden-Württemberg with little consideration for keeping sisters and other relatives in proximity to one another. Two sisters living hours away from each other described how they had repeatedly pleaded to be relocated closer together, while acknowledging that the authorities have responded positively to other similar requests. Additionally, several women explained that the Heimat (residence) where they were staying was a kind of convent run by nuns who sometimes did not permit them to go out or receive visitors.

Here it is interesting to examine the basis for exclusion of adult men from participation in travel to Baden-Württemberg, and by extension in the healing process for the female survivors the programme aims to support. Indeed, the complaint that husbands and adult sons were unable to accompany the women was consistently heard during my interviews with participants. Likewise, a journalist who covered the programme from both Duhok and Germany stated that this was “the one complaint about the program many of the women raised to me.” This article considers three main factors as contributing to and possibly explaining the “women-only” design of the Baden-Württemberg programme, each bringing implications for the gendered construction of the Yezidi survivor:

1) dominant discourse on female victimization;

2) perceptions about the optimal conditions for women’s recovery

3) structural limitations informed by wider migration dynamics and discourse in Germany.

All this suggests that on" paper " the project was ready to accept Yazidi women, but in fact it turned out that all the nuances were not fully thought out.

Tags: #yazidisinfo #newsyazidi #aboutyazidi #genocideyazidi #yazidigermany